Get the Facts About Underage Drinking

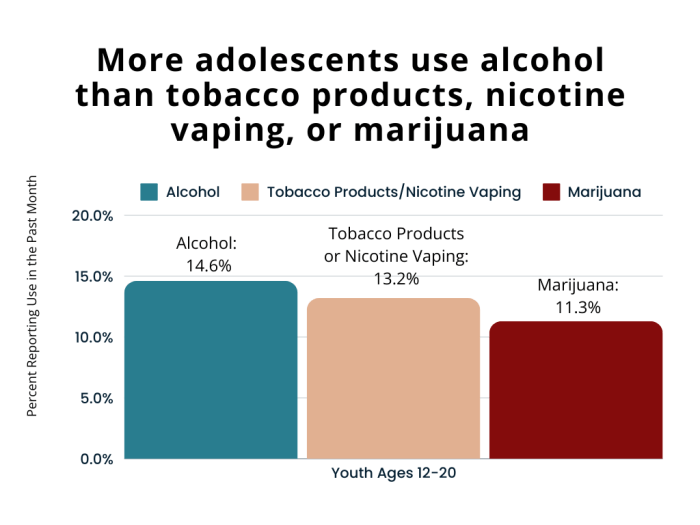

Underage drinking is a serious public health problem in the United States. Alcohol is the most widely used substance among America’s youth and can cause them enormous health and safety risks.

The consequences of underage drinking can affect everyone—regardless of age or drinking status.

Either directly or indirectly, we all feel the effects of the aggressive behavior, property damage, injuries, violence, and deaths that can result from underage drinking. This is not simply a problem for some families—it is a nationwide concern.

Underage Drinking Statistics

Many Youth Drink Alcohol

-

In 2023, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), about 19.9% of youth ages 14 to 15 reported having at least one drink in their lifetime.1

-

In 2023, 5.6 million youth ages 12 to 20 reported drinking alcohol beyond “just a few sips” in the past month.2

-

Adolescent alcohol use differs by race and ethnicity. For example, at age 14, White, Black, and Hispanic youth are equally likely to drink. By age 18, White and Hispanic youth are twice as likely to drink than Black youth.3

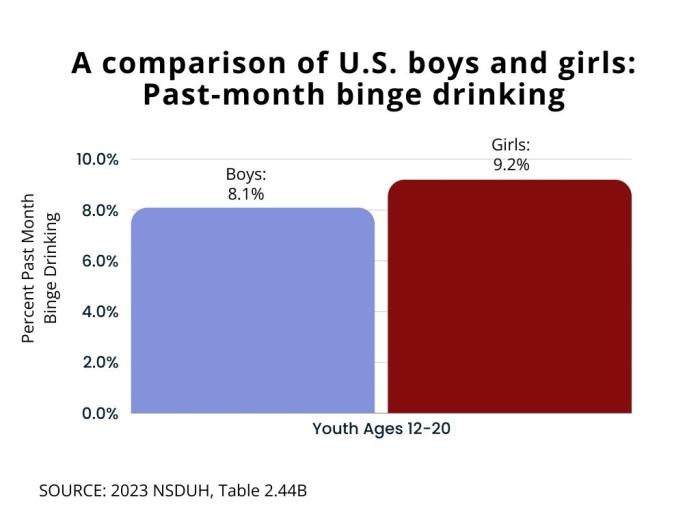

Youth Often Binge Drink

People ages 12 to 20 drink 3.0% of all alcohol consumed in the United States. Although youth drink less often than adults, when they do drink, they drink more. Approximately 91% of all beverages containing alcohol consumed by youth are consumed by youth who engage in binge drinking (see the "What Is Binge Drinking?" box).4

-

In 2023, 3.3 million youth ages 12 to 20 reported binge drinking at least once in the past month.2

-

In 2023, approximately 663,000 youth ages 12 to 20 reported binge drinking on five or more days over the past month.2

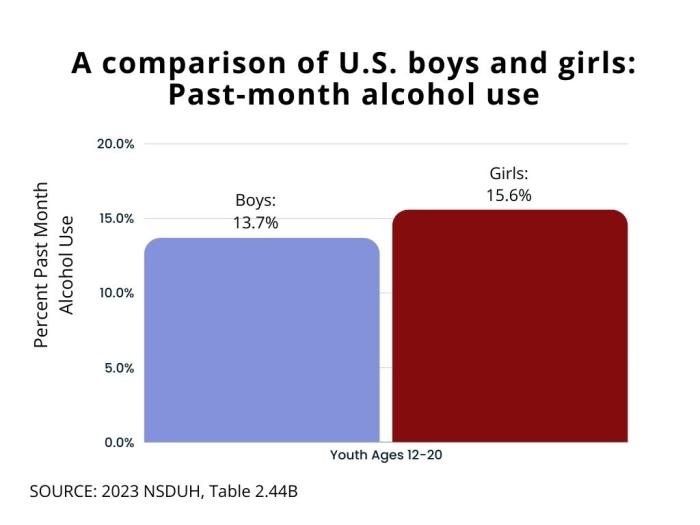

Drinking Patterns Vary by Age and Sex

Alcohol use often begins during adolescence and becomes more likely as adolescents age. In 2023, about one in 100 adolescents ages 12 to 13 reported drinking alcohol in the past month, and about one in 200 engaged in binge drinking.5 Among respondents ages 16 to 17, fewer than one in five reported drinking, and fewer than one in 10 reported binge drinking.5 Implementing prevention strategies during early adolescence is needed to prevent this escalation, particularly because earlier alcohol use is associated with a higher likelihood of a variety of alcohol-related consequences.6

Historically, adolescent boys were more likely to drink and binge drink than girls. Now, that relationship has reversed. Past-month alcohol use among adolescents ages 12 to 17 has declined more in recent years for boys than girls.7 Now, more girls report more alcohol use (7.9% for girls vs. 6.0% for boys) and binge drinking (4.5% for girls vs. 3.3% for boys).8,9

Underage Drinking Is Dangerous

Underage drinking poses a range of risks and negative consequences. It is dangerous because it:

- Causes many deaths. Alcohol is a significant factor in the deaths of people younger than age 21 in the United States each year. This includes deaths from motor vehicle crashes, homicides, alcohol overdoses, falls, burns, drowning, and suicides.

- Causes many injuries. Drinking alcohol can cause youth to have accidents and get hurt. In 2011 alone, about 188,000 people younger than age 21 visited an emergency room for alcohol-related injuries.10

- Impairs judgment. Drinking can lead to poor decisions about taking risks, including unsafe sexual behavior, drinking and driving, and aggressive or violent behavior.

- Increases the risk of physical and sexual assault. Underage binge drinking is associated with an increased likelihood of being the victim or perpetrator of interpersonal violence.11

- Can lead to other problems. Drinking may cause youth to have trouble in school or with the law. Drinking alcohol is also associated with the use of other substances.

- Increases the risk of alcohol problems later in life. Research shows that people who start drinking before the age of 15 are at a higher risk for developing alcohol use disorder (AUD) later in life. For example, adults ages 26 and older who began drinking before age 15 are 3.6 times more likely to report having AUD in the past year than those who waited until age 21 or later to begin drinking.12

- Interferes with brain development. Research shows that people’s brains keep developing well into their 20s. Alcohol can alter this development, potentially affecting both brain structure and function. This may cause cognitive or learning problems as well as may increase vulnerability for AUD, especially when people start drinking at a young age and drink heavily.13,14

Why Do So Many Youth Drink?

As children mature, it is natural for them to assert their independence, seek new challenges, and engage in risky behavior. Underage drinking is one such behavior that attracts many adolescents. They may want to try alcohol but often do not fully recognize its effects on their health and behavior. Other reasons youth drink alcohol include:

-

Peer pressure

-

Increased independence or the desire for it

-

Stress

In addition, many youth have easy access to alcohol. In 2023, among adolescents ages 15 to 17 who reported drinking alcohol in the past month, 84.3% reported getting it for free the last time they drank.15 In many cases, adolescents have access to alcohol through family members or find it at home.

What Is Binge Drinking?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking as a pattern of drinking alcohol that brings blood alcohol concentration (BAC) to 0.08%—or 0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter—or higher. For a typical adult, this pattern corresponds to consuming five or more drinks (male), or four or more drinks (female), in about two hours.16 Research shows that fewer drinks in the same timeframe result in the same BAC in youth: only three drinks for girls, and three to five drinks for boys, depending on their age and size.17 In the United States, a "standard drink" is defined as any beverage containing 0.6 fl oz or 14 grams of pure alcohol.

Preventing Underage Drinking

Preventing underage drinking is a complex challenge. Any successful approach must consider many factors, including:

-

Genetics

-

Personality

-

Rate of maturation and development

-

Level of risk

-

Social factors

-

Environmental factors

Several key approaches have been found to be successful. They are:

- Individual-level interventions. This approach seeks to change the way youth think about alcohol so they are better able to resist pressures to drink.

- School-based interventions. These are programs that provide students with the knowledge, skills, motivation, and opportunities they need to remain alcohol-free.

- Family-based interventions. These are efforts to empower parents to set and enforce clear rules against drinking, as well as improve communication between children and parents about alcohol.

- Community-based interventions. Community-based interventions are often coordinated by local coalitions working to mitigate risk factors for alcohol misuse.

- Policy-level interventions. This approach makes alcohol harder to get—for example, by raising the price of alcohol and keeping the U.S. Minimum Legal Drinking Age at 21. Enacting zero-tolerance laws that outlaw driving after any amount of drinking for people younger than 21 can also help prevent problems.

The Role Parents Play

Parents and teachers can play a meaningful role in shaping youth’s attitudes toward drinking. Parents, in particular, can have either a positive or negative influence.

Parents can help their children avoid alcohol problems by:

-

Talking about the dangers of drinking

-

Drinking responsibly if they choose to drink

-

Serving as positive role models in general

-

Not making alcohol available

-

Getting to know their children’s friends

-

Having regular conversations about life in general

-

Connecting with other parents about sending clear messages about the importance of youth not drinking alcohol

-

Supervising all parties to make sure there is no alcohol

-

Encouraging kids to participate in healthy and fun activities that do not involve alcohol

Research shows that children of actively involved parents are less likely to drink alcohol.18 However, if parents provide alcohol to their kids (even small amounts), have positive attitudes about drinking, and engage in alcohol misuse, adolescents have an increased risk of misusing alcohol. Moreover, if the adolescent has a parent with AUD, they are less likely to be protected from alcohol misuse through parental engagement and other factors.19

Warning Signs of Underage Drinking

Adolescence is a time of change and growth, including behavior changes. These changes usually are a normal part of growing up but sometimes can point to an alcohol problem. Parents, families, and teachers should pay close attention to the following warning signs that may indicate underage drinking:20,21

-

Changes in mood, including anger and irritability

-

Academic or behavioral problems in school

-

Rebelliousness

-

Changing groups of friends

-

Low energy level

-

Less interest in activities or care in appearance

-

Finding alcohol among an adolescent's belongings

-

Smelling alcohol on an adolescent's breath

-

Problems concentrating or remembering

-

Slurred speech

-

Coordination problems

Treating Underage Drinking Problems

Screening youth for alcohol use and AUD is very important and may prevent problems down the road. Screening by a primary care provider or other health practitioner (e.g., pediatrician) provides an opportunity to identify problems early and address them before they escalate. It also allows adolescents to ask questions of a knowledgeable adult. NIAAA and the American Academy of Pediatrics both recommend that all youth be regularly screened for alcohol use.

Some youth can experience serious problems as a result of drinking, including AUD, which require intervention by trained professionals. Professional treatment options include:

- Attending individual or group counseling sessions one or more times per week

- Receiving a prescription from a primary care provider or psychiatrist to help reduce alcohol cravings

- Participating in family therapy to build a supportive foundation for recovery

For more information, please visit: niaaa.nih.gov

1. SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (CBHSQ). 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.8B—Alcohol use in lifetime, past year, and past month: among people aged 12 or older; by detailed age category, percentages, 2022 and 2023. [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

2. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.9A—Alcohol, binge alcohol, and heavy alcohol use in past month: among people aged 12 or older; by detailed age category, numbers in thousands, 2022 and 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

3. Chen CM, Yoon YH. NIAAA Surveillance Report #116: Trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2019. Figure 1-5. NSDUH: Prevalence of drinking in the past 30 days among 12- to 20-year-olds, by age, sex, and race/Hispanic origin. Sterling, VA: CSR, Inc.; 2021 March [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance-reports/surveillance116

4. Calculated using past 30-day quantity and frequency of alcohol use and past 30-day frequency of binge drinking (four or more drinks for females and five or more drinks for males on the same occasion) from the 2023 NSDUH public-use data file. SAMHSA, CBHSQ [Internet]. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH-2023-DS0001). Public-use file dataset. [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh/datafiles

5. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.9B—Alcohol, binge alcohol, and heavy alcohol use in past month: among people aged 12 or older; by detailed age category, percentages, 2022 and 2023 [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

6. Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009 Jun;123(6):1477–484. PubMed PMID: 19482757

7. Chen CM, Yoon YH. Surveillance Report #116: Trends in underage drinking in the United States, 1991–2019. Bethesda, MD: NIAAA; 2021 March [cited 2024 Oct 2]. Available from: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/surveillance-reports/surveillance116

8. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.27B—Alcohol use in past month: among people aged 12 or older; by age group and demographics, percentages, 2022 and 2023. [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

9. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 2.28B—Binge alcohol use in past month: among people aged 12 or older; by age group and demographics, percentages, 2022 and 2023. [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

10. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. The DAWN Report: Alcohol and drug combinations are more likely to have a serious outcome than alcohol alone in emergency department visits involving underage drinking. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2014 [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/spot143-underage-drinking-2014/spot143-underage-drinking-2014/spot143-underage-drinking-2014.pdf

11. Waterman EA, Lee KDM, Edwards KM. Longitudinal associations of binge drinking with interpersonal violence among adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Jul;48:1342–52, 2019. PubMed PMID: 31079263

12. Age at drinking onset: age when first drank a beverage containing alcohol (a can or bottle of beer, a glass of wine or a wine cooler, a shot of liquor, or a mixed drink with liquor in it), not counting a sip or two from a drink. AUD: having met two or more of the 11 AUD diagnostic criteria according to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). AUD risk across different ages at drinking onset is compared using the prevalence ratio weighted by the person-level analysis weight. Derived from the CBHSQ 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH-2023-DS0001) public-use file. [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh/datafiles

13. Squeglia LM, Tapert SF, Sullivan EV, Jacobus J, Meloy MJ, Rohlfing T, Pfefferbaum A. Brain development in heavy-drinking adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Jun;172(6):531–42, 2015. PubMed PMID: 25982660

14. Pfefferbaum A, Kwon D, Brumback T, Thompson WK, Cummins K, Tapert SF, Brown SA, Colrain IM, Baker FC, Prouty D, De Bellis MD, Clark DB, Nagel BJ, Chu W, Park SH, Pohl KM, Sullivan EV. Altered brain developmental trajectories in adolescents after initiating drinking. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;175(4):370–80. PubMed PMID: 29084454

15. SAMHSA, CBHSQ. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 8.20B—Source where alcohol was obtained for most recent use in past month: among past month alcohol users aged 12 to 20, by age group and sex: Percentages, 2022 and 2023. [cited 2024 Aug 23]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-detailed-tables

16. NIAAA. Defining binge drinking. What colleges need to know now: an update on college drinking. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health; 2007 Nov. Defining binge drinking, p. 2. [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.collegedrinkingprevention.gov/media/1College_Bulletin-508_361C4E.pdf

17. Chung T, Creswell KG, Bachrach R, Clark DB, Martin CS. Adolescent binge drinking: developmental context and opportunities for prevention. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):5–15. PubMed PMID: 30557142

18. van der Vorst H, Engels RC, Meeus W, Deković M. The impact of alcohol-specific rules, parental norms about early drinking and parental alcohol use on adolescents’ drinking behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;47(12):1299–306. PubMed PMID: 17176385

19. Yap M, Cheong T, Zaravinos-Tsakos F, Lubman DI, Jorm, A. Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction. 2017 Jul;112(7):1142–62, 2017. PubMed PMID: 28178373

20. Rusby JC, Light JM, Crowley R, Westling E. Influence of parent-youth relationship, parental monitoring, and parent substance use on adolescent substance use onset. J Fam Psychol. 2018 Apr;32(3):310–20. PubMed PMID: 29300096

21. SAMHSA [Internet]. How to tell if your child is drinking alcohol. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; [updated 2022 Apr 14; cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/underage-drinking/parent-resources/how-tell-if-your-child-drinking-alcohol