The Basics: Defining How Much Alcohol is Too Much

Step 1 - Read the Article

- What counts as a drink?

- How many drinks are in common containers?

- When is having any alcohol too much?

- What are the U.S. Dietary Guidelines on alcohol consumption?

- What is heavy drinking?

- What is the clinical utility of the “heavy drinking day” metric?

- Resources

- References

Step 2 - Complete the Brief Continuing Education Post-Test

Takeaways

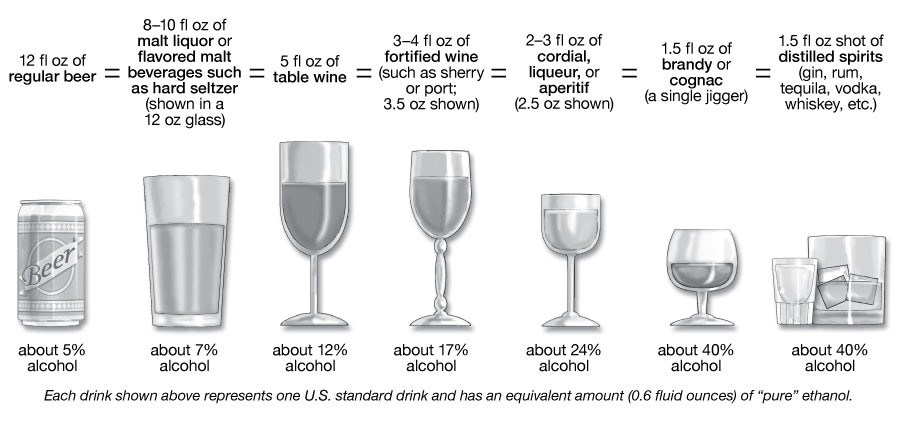

- Show your patients a standard drink chart when asking about their alcohol consumption to encourage more accurate estimates. Drinks often contain more alcohol than people think, and patients often underestimate their consumption.

- Advise some patients not to drink at all, including those who are managing health conditions that can be worsened by alcohol, are taking medications that could interact with alcohol, are pregnant or planning to become pregnant, or are under age 21.

- Otherwise, advise patients who choose to drink to follow the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, by limiting intake to 1 drink or less for women and 2 drinks or less for men—on any single day, not on average. Drinking at this level may reduce, though not eliminate, risks.

- Don’t advise non-drinking patients to start drinking alcohol for their health. Past research overestimated benefits of moderate drinking, while current research points to added risks, such as for breast cancer, even with low levels of drinking.

How much, how fast, and how often a person drinks alcohol all factor into the risk for alcohol-related problems. How much and how fast a person drinks influences how much alcohol enters the bloodstream, how impaired he or she becomes, and what the related acute risks will be. Over time, how much and how often a person drinks influences not only acute risks but also chronic health problems, including liver disease and alcohol use disorder (AUD), and social harms such as relationship problems.1 (See Core articles on medical complications and AUD.)

It can be hard for patients to gauge and accurately report their alcohol intake to clinicians, in part because labels on alcohol containers typically list only the percent of alcohol by volume (ABV) and not serving sizes or the number of servings per container. Whether served in a bar or restaurant or poured at home, drinks often contain more alcohol than people think. It’s easy and common for patients to underestimate their consumption.2,3

While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, general guidelines can help clinicians advise their patients and minimize the risks. Here, we will provide basic information about drink sizes, drinking patterns, and alcohol metabolism to help answer the question “how much is too much?” In short, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better.

What counts as a drink?

In the United States, a "standard drink" or "alcoholic drink equivalent" is any drink containing 14 grams, or about 0.6 fluid ounces, of “pure” ethanol. As shown in the illustration, this amount is found in 12 ounces of regular beer (with 5% alcohol by volume or alc/vol), 5 ounces of table wine (with 12% alc/vol), or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (with 40% alc/vol).

The sample standard drinks above are just starting points for comparison, because actual alcohol content and customary serving sizes can vary greatly both across and within types of beverages. For example:

- Beer: The most popular type of beer is light beer, which may be light in calories, but not necessarily in alcohol. The mean alc/vol for light beers is 4.3%, almost as much as a regular beer with 5% alc/vol.4 On average, craft beers have more than 5% alc/vol and flavored malt beverages, such as hard seltzers, more than 6% alc/vol.4 Some craft beers and flavored malt beverages have in the range of 8-9% alc/vol. Advise patients to check container labels for the alcohol content and adjust their intake accordingly.

- Wine: The largest category of wine is table wine. On average, table wines contain about 12% alc/vol4 and can range from about 5% to 16%. Larger wine glasses can encourage larger pours. People are often unaware that a 25-ounce (750ml) bottle of table wine with 12% alc/vol contains five standard drinks, and one with 14% alc/vol holds nearly six.

- Cocktails: Recipes for cocktails often exceed one standard drink’s worth of alcohol. The cocktail content calculator on Rethinking Drinking shows the alcohol content in sample cocktails.

Showing your patients a standard drink chart (printable here [PDF – 184 KB]) will help inform them about drink equivalents and may help your patients to estimate their consumption more accurately.

How many drinks are in common containers?

Below is the approximate number of standard drinks in different sized containers of beer, malt liquor, table wine, and distilled spirits:

| regular beer (5% alc/vol) |

malt liquor (7% alc/vol) |

table wine (12% alc/vol) |

80-proof distilled spirits (40% alc/vol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 fl oz = 1 16 fl oz = 1⅓ 22 fl oz = 2 40 fl oz = 3⅓ |

12 fl oz = 1½ 16 fl oz = 2 22 fl oz = 2½ 40 fl oz = 4½ |

750 ml (a regular wine bottle) = 5 |

a shot (1.5 oz glass/50 ml bottle) = 1 |

See the drink size calculator on NIAAA’s Rethinking Drinking website for more examples.

When is having any alcohol too much?

It is safest for patients to avoid alcohol altogether if they:

- Take medications that interact with alcohol (see Core article on medication interactions).

- Have a medical condition caused or exacerbated by drinking, such as liver disease, bipolar disorder, abnormal heart rhythm, diabetes, hypertension, or chronic pain, among others (see Core article on medical complications).

- Are under the legal drinking age of 21.

- Plan to drive a vehicle or operate machinery.

- Are pregnant or trying to become pregnant.

- Experience facial flushing and dizziness when drinking alcohol. Between 30% and 45% of people of East Asian heritage inherit gene variants responsible for an enzyme deficiency that causes these symptoms and amplifies the risk of alcohol-related cancers, particularly head and neck cancer and esophageal cancer, even if they drink at light or moderate levels.5 People of other races and ethnicities can carry similar variants.6

What are the U.S. Dietary Guidelines on alcohol consumption?

The U.S. Dietary Guidelines7 recommends that for healthy adults who choose to drink and do not have the exclusions noted above, alcohol-related risks may be minimized, though not eliminated, by limiting intakes to:

- For women—1 drink or less in a day

- For men—2 drinks or less in a day

The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines makes it clear that these light to moderate amounts are not intended as an average, but rather the amount consumed on any single day.

The latest and most rigorous research casts some doubt on past studies that linked light to moderate drinking with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease and indicates that protective effects were overestimated.8–10 Earlier study methods made it difficult to conclude whether positive cardiovascular outcomes were due to low alcohol consumption or instead, for example, to diet, genetics, health history, or behavioral differences between people who do and do not drink. Recent studies also suggest that that even drinking in moderation increases the risk for stroke,11 cancer,12 and premature death.13,14

In short, current research indicates that: (1) for those who drink, the less, the better;15 (2) those with a strong family history of cancer or AUD may wish to minimize risk by abstaining;13 and (3) those who don’t drink alcohol shouldn’t start—as noted in the U.S. Dietary Guidelines—"for any reason."7

What is heavy drinking?

The patterns below are considered “heavy” drinking,16,17 which markedly increases the likelihood of AUD and other alcohol-related harms:1

- For women—4 or more drinks on any day or 8 or more per week

- For men—5 or more drinks on any day or 15 or more per week

Heavy drinking thresholds for women are lower because after consumption, alcohol distributes itself evenly in body water, and pound for pound, women have proportionally less water in their bodies than men do. This means that after a woman and a man of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

For men and women, the risk for alcohol-related harm depends on a combination of how much, how fast, and how often they drink:

- Too much, too fast. When a woman has 4 or more drinks—or a man has 5 or more—in about 2 hours, this typically raises the BAC to 0.08% and meets the definition of binge drinking.16 Binge drinking causes more than half of the alcohol-related deaths in the U.S.18 It increases the risk of falls, burns, car crashes, memory blackouts, medication interactions, assaults, drownings, and overdose deaths18 (see Core article on medication interactions).

- Too much, too often. Frequent heavy drinking raises the risk for both acute harms, such as falls and medication interactions, and for chronic consequences, such as AUD1 and dose-dependent increases in liver disease,1 heart disease,19 and cancers20 (see Core article on medical complications).

The odds are good that many of your patients drink heavily. Binge drinking occurs in about half of adolescents and adults who drink,21,22 and in about 1 in 4 adults over age 65 who drink,23 and is increasing among women.24,25 Given the prevalence and risks, it is important to screen all patients for heavy drinking and intervene as needed. (See Core article on screening and assessment.)

Many patients may think that heavy drinking is not a concern because they can “hold their liquor.” However, having an innate “low level of response” or “high tolerance” to alcohol is a reason for caution, as people with this trait tend to drink more and thus have an increased risk for alcohol-related problems including AUD.26 Patients who drink within the Dietary Guidelines, too, may be unaware that even if they don’t feel a “buzz,” driving can be impaired.27

What is the clinical utility of the “heavy drinking day” metric?

Knowing what counts as a heavy drinking day—4 or more drinks for women and 5 or more for men—can be clinically useful in two ways. First, brief screening tools recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force—such as the AUDIT-C and the NIAAA single alcohol screening question—ask about heavy drinking days.28 (See Core article on screening and assessment.) These tools allow you to identify the patients who need your advice and assistance to cut down or quit.

Second, when offering advice to patients who drink heavily, you may help motivate them to cut back or quit by sharing that having no heavy drinking days can bring marked improvements in how they feel and function.29 In studies, the gains were strong enough to prompt the FDA to accept no heavy drinking days as a positive outcome in alcohol treatment trials, in addition to the outcome of abstinence, the safest route.30 (See the Core article on brief intervention.)

It also helps to be aware of the typical weekly volume, because the more frequent the heavy drinking days, and the greater the weekly volume, the greater the risk for having AUD.31 (See Core article on screening and assessment.)

In closing, to gauge how much alcohol is too much for patients, you will need to look at their individual circumstances and assess the risks and health effects. At one end of the spectrum, any alcohol is too much for some patients, as noted above. At the other end, patterns such as heavy and binge drinking are clearly high risk and should be avoided. In the zone in between, for people who choose to drink, current research indicates the less, the better.8,9

Other Core articles will help you to screen for heavy drinking, identify possible medical complications of alcohol use, assess for signs of AUD, and conduct a brief intervention to guide patients in setting a plan to cut back or quit if needed.

The Basics of How the Body Processes Alcohol

Absorption and distribution. When alcohol is consumed, it passes from the stomach and intestines into the bloodstream, where it distributes itself evenly throughout all the water in the body’s tissues and fluids. Drinking alcohol on an empty stomach increases the rate of absorption, resulting in higher blood alcohol level, compared to drinking on a full stomach. In either case, however, alcohol is still absorbed into the bloodstream at a much faster rate than it is metabolized. Thus, the blood alcohol concentration builds when a person has additional drinks before prior drinks are metabolized.

Metabolism. The body begins to metabolize alcohol within seconds after ingestion and proceeds at a steady rate, regardless of how much alcohol a person drinks or of attempts to sober up with caffeine or by other means. Most of the alcohol is broken down in the liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). ADH transforms ethanol, the type of alcohol in alcohol beverages, into acetaldehyde, a toxic, carcinogenic compound. Generally, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down to a less toxic compound, acetate, by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH). Acetate then is broken down, mainly in tissues other than the liver, into carbon dioxide and water, which are easily eliminated. To a lesser degree, other enzymes (CYP2E1 and catalase) also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde.

Although the rate of metabolism is steady in any given person, it varies widely among individuals depending on factors including liver size and body mass, as well as genetics. Some people of East Asian descent, for example, carry variations of the genes for ADH or ALDH that cause acetaldehyde to build up when alcohol is consumed, which in turn produces a flushing reaction and increases cancer risk.28–30 People of other races and ethnicities can also carry variations in these genes.6

Blood alcohol concentration (BAC). BAC is largely determined by how much and how quickly a person drinks alcohol as well as by the body’s rates of alcohol absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Binge drinking is defined as reaching a BAC of 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or higher. A typical adult reaches this BAC after consuming 4 or more drinks (women) or 5 or more drinks (men), in about 2 hours.

For more details about alcohol metabolism, see this video and this summary.

We invite healthcare professionals to complete a post-test to earn FREE continuing education credit (CME/CE or ABIM MOC). This continuing education opportunity is jointly provided by the Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and NIAAA. Learn more about credit designations here.

There are two credit paths—please choose the one that aligns with your profession.

These professionals can earn 0.75 credits for reading this single article:

- Physicians (and others who can earn AMA credit)

- Physician Assistants

- Nurses

- Pharmacists

To earn AMA, AAPA, ANCC, ACPE, or ABIM MOC credit, review this article, then use the link below to log into or create a CME University account. Answer 3 out of 4 questions correctly on the post-test to earn 0.75 credits.

These professionals can earn 1.5 credits for reading a pair of articles as indicated below:

- Licensed Psychologists (and others who can earn APA credit)

- Social Workers

To earn APA or ASWB credit, review this article and Topic 2—Risk Factors: Varied Vulnerability to Alcohol-Related Harm, then use the link below to log into or create a CME University account. Answer 7 out of 10 questions correctly on the combined post-test to earn 1.5 credits.

Released on 5/6/2022

Expires on 5/10/2025

Learning Objectives

After completing this activity, the participant should be better able to:

- Assist patients in accurately estimating their alcohol intake.

- Identify the categories of patients who need advice to avoid alcohol altogether.

- Counsel patients on guideline-concordant limits for alcohol consumption.

Contributors

Contributors to this article for the NIAAA Core Resource on Alcohol include the writers for the full article, content contributors to subsections, reviewers, and editorial staff. These contributors included both experts external to NIAAA as well as NIAAA staff.

NIAAA Writers and Content Contributors

Raye Z. Litten, PhD

Editor and Content Advisor for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Director, Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

Laura E. Kwako, PhD

Editor and Content Advisor for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Health Scientist Administrator,

Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

Maureen B. Gardner

Project Manager, Co-Lead Technical Editor, and

Writer for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

External Reviewers

Louis E. Baxter Sr., MD, DFASAM

Assistant Professor Medicine, ADM

Fellowship Director, Howard University

Hospital, Washington, DC;

Assistant Clinical Professor Medicine

Rutgers Medical School, Newark, NJ

Douglas Berger MD, MLitt

Staff Physician, VA Puget Sound,

Associate Professor of Medicine,

University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Barbara J. Mason, PhD

Pearson Family Professor,

The Scripps Research Institute, CA

Kenneth J. Sher, PhD

Curators’ Distinguished Professor of

Psychological Sciences,

University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

NIAAA Reviewers

George F. Koob, PhD

Director, NIAAA

Patricia Powell, PhD

Deputy Director, NIAAA

Nancy Diazgranados, MD, MS, DFAPA

Deputy Clinical Director, NIAAA

Lorenzo Leggio, MD, PhD

NIDA/NIAAA Senior Clinical Investigator and Section Chief;

NIDA Branch Chief;

NIDA Deputy Scientific Director;

Senior Medical Advisor to the NIAAA Director

Falk W. Lohoff, MD

Lasker Clinical Research Scholar;

Chief, Section on Clinical Genomics and Experimental Therapeutics, NIAAA

Aaron White, PhD

Senior Scientific Advisor to

the NIAAA Director, NIAAA

Editorial Team

NIAAA

Raye Z. Litten, PhD

Editor and Content Advisor for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Director, Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

Laura E. Kwako, PhD

Editor and Content Advisor for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Health Scientist Administrator,

Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

Maureen B. Gardner

Project Manager, Co-Lead Technical Editor, and

Writer for the Core Resource on Alcohol,

Division of Treatment and Recovery, NIAAA

Contractor Support

Elyssa Warner, PhD

Co-Lead Technical Editor,

Ripple Effect

Daria Turner, MPH

Reference and Resource Analyst,

Ripple Effect

Kevin Callahan, PhD

Technical Writer/Editor,

Ripple Effect

To learn more about CME/CE credit offered as well as disclosures, visit our CME/CE General Information page. You may also click here to learn more about contributors.